As universities seek to strengthen their connections with their local communities, concepts like ’civic universities’ and ’public engagement’ can play a key role. To help inspire their members, the Swedish non-profit organisations VA (Public & Science) and Unilink jointly ran an online conference on 12 November, to gain a better understanding of these concepts in practice.

Around 27 different research institutions were represented by participants at the event, which featured a combination of presentations, breakout discussions and participant input. As highlighted by a number of the speakers, civic place-based engagement has become even more critical in light of the corona pandemic, where universities have a central role in supporting and engaging with their local communities in many different ways.

Civic universities – a strategic approach

The first half of the programme focused on ‘civic universities’, and was facilitated by Fredrik Sjögren from University West. Professor John Goddard, Emeritus Professor of Regional Development Studies, Newcastle University, and Vice Chair of the Civic University Commission, described how the Civic University Network has come about in the UK. The network was one of the key recommendations from the UPP Foundation’s Civic University Commission, an independent inquiry in 2018-2019 into the future of the civic universities and how they can best serve their ‘place’ in the 21st century. To date, almost 100 Vice-Chancellors from a diverse range of UK universities have committed to producing Civic University Agreements.

John stressed that becoming a civic university is a strategic approach that requires institutional change led from the top and the adoption of a holistic engagement and place strategy that is co-created with local partners from the public, private and voluntary sectors. Values and local accountability are particularly important so that a university becomes the University ‘of’ a particular city rather than just being located ‘in’ a city. He highlighted seven key dimensions of a civic university: a sense of purpose; active engagement; holistic approach; sense of place; willingness to invest; transparency and accountability; and innovative methodologies.

One university committed to being a civic university is the University of Glasgow. Des McNulty, Assistant Vice-Principal, Economic Development and Civic Engagement, provided an overview of the University of Glasgow’s approach, which is based around the three ‘C’s of civic engagement – connect, collaborate, contribute. Using the University’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic as a case study, he talked about ways in which Covid-19 has increased inter-university collaboration as well as collaboration between universities and other civic partners. Examples include health; tackling disadvantage; green recovery; and digital and data analytics. Des stressed that universities are anchor institutions within the local and regional economy, as well as centres of learning, which need to work in partnership across geographies to better support ‘left behind’ places.

Civis – a European alliance of civically engaged universities

To provide a broader European perspective, Fredrik Oldsjö, Secretary General of the European Civic University Alliance – Civis, at Stockholm University, talked about the role of the Alliance and how it is enhancing collaborations between universities at local, regional and European level. Civis is an alliance between eight civically engaged Universities across Europe (including Stockholm University), funded through the European Commission’s European Universities Initiative. Fredrik explained how Civis is designed not just as a network but to support a different kind of working that involves building transnational alliances between universities and adopting a challenge-based approach to the way in which students, academics and external partners cooperate on societal challenges. Through the European Universities Initiative there are now 41 alliances involving 279 member universities, 11 of which are Swedish.

Participants were then invited to reflect in groups on how civic they felt their own institutions were. Discussions highlighted a number of challenges including difficulties embedding civic engagement into institutional frameworks, promoting bottom up initiatives in top down organisations, and how it requires both an individual and organisational approach.

The importance of engaging with the public

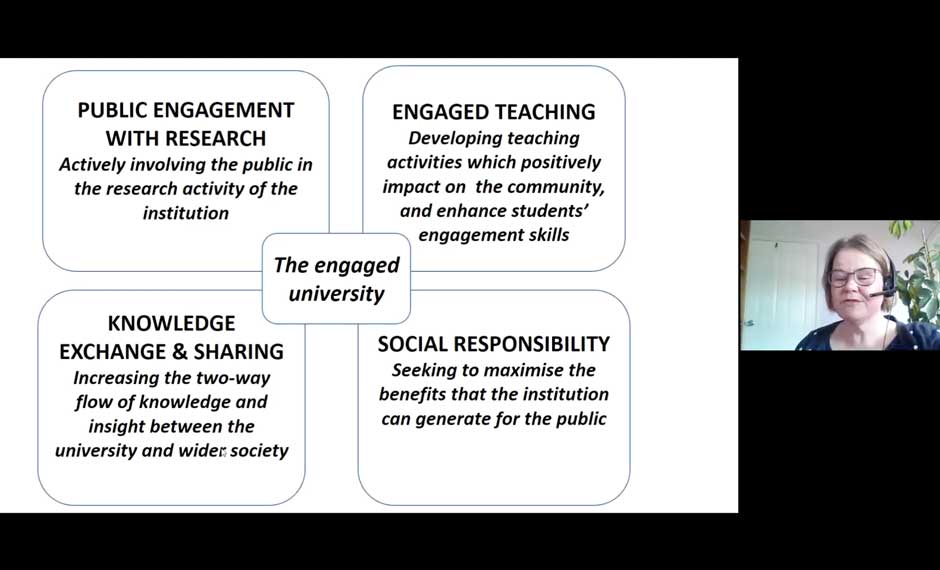

The second half of the programme had a specific focus on ‘public engagement’, and was facilitated by Cissi Askwall, Secretary General of VA (Public & Science). Maria Hagardt, International Relations & Communications Manager at VA provided an overview of what is meant by ‘public engagement’, referring to the NCCPE’s definition of public engagement as “a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit”. She also talked about why public engagement matters and provided examples of activities, processes and methods.

Participants also heard about how public engagement has evolved within higher education in the UK from Sophie Duncan, Director of the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement that seeks to inspire and support universities to engage with the public. Sophie also highlighted the importance of having a strong public engagement strategy (e.g. trust, accountability, social responsibility and relevance). One of NCCPE’s key roles is inspiring culture change within universities, where the NCCPE’s Edge tool for supporting institutional change plays a particular role. NCCPE also undertakes activities to support the professional development of public engagement professionals as well as reward and recognise effective public engagement practices.

Inspiring public engagement practices

Susan Grant, Community and Public Engagement Coordinator, at Glasgow Caledonian University then provided an inspiring overview of how her University works with community and public engagement on the ground. Community and Public Engagement at GCU was formally established in 2012 when it signed the NCCPE ‘Engaged University’ manifesto. Since then they have worked with 601 internal and external partners to deliver 232 activities and engage 22,000 members of the public. Susan provided a taster of some of their public engagement activities, also describing how they have had to quickly move to online engagement during the corona pandemic. Susan stressed how partnerships are critical to their work with local communities plus the role of volunteers.

Helen Garrison, Project & Communications Manager at VA, provided a brief introduction to Science Shops and how they are an effective model for developing mutually beneficial relationships between universities and local communities. She also highlighted the work of the Living Knowledge network and the EU SciShops project to support Science Shops.

Anne Laybourne then introduced the Community Research Initiative for Students at University College London, which she manages. CRIS matchmakes Masters students with local charities and community organisations to conduct research for their dissertations, and now has partnerships with 400 non-profit organisations in London.

Similarities and differences between the UK and Sweden

In breakout rooms, participants were invited to reflect upon how their organisations might do more public engagement and the support that they need. Key points raised included the need for more recognition and rewards, dedicated funded roles, better communication internally and externally, internal structures to support public engagement, and for public engagement to be prioritised. Discussions also highlighted both similarities and differences between how public engagement is supported in the UK and Sweden. Societal engagement is an integral part of the work of universities in both countries, but the way it is organised often differs. Many UK universities have public engagement departments, whereas support for this type of work usually comes from communication departments at Swedish universities. The usual Swedish translation of ‘public engagement’ – ‘samverkan’ (societal collaboration) is also a much broader concept, encompassing industrial-academic partnerships too.

“Having had to put Unilink’s intended study trip to Scotland this autumn on hold, this event provided an excellent forum for knowledge exchange and the sharing of best practices,” commented Petra Norling, chair of Unilink. “By holding it online we were also able to open it up to a much wider audience and feedback has shown that many participants have gained new inspiration and contacts as a result of the exchange too,” she added.